Welcome friends, been a while.

In my return to substack, I will discuss the hot topic of the day — new token launches.

Specifically, this post is the first of a 3 part series focusing on issues and misconceptions in the market around new tokens commonly described as “low float, high FDV”.

Well, at least I think this is going to end up as a three-part substack series. There’s a lot of stuff to discuss and I am not known for being succinct. But perhaps I will get too lazy to finish the whole thing and it will be two parts instead. We will see.

Before we begin – if you’re struggling to know what I’m talking about in this post, a previous post I wrote in 2021 is potentially helpful pre-reading: On the meme of market caps and unlocks, by cobie

And as always, please remember: I am not a financial advisor, I am a biased and flawed human being, I am washed up, I am an idiot, I am mentally beyond my peak and declining into my twilight years, I am stumbling through the world trying to make sense of everything and very rarely succeeding at that. I am literally a participant in the crypto industry which means it is unlikely my IQ is even close to double digits. I try not to write too much about coins that I own but will disclose throughout the article when I do. Did you guys hear RoaringKitty was back and he posted like fifty sick Avengers clips? Okay anyway.

When I wrote that post 3 years ago, I assumed it was the last time I’d probably ever write about the float, FDV and market cap games. Perhaps naively, I expected market participants to become more sophisticated regarding these important dynamics.

Instead, they ended up picking these new coins as the “best coins to long” citing “no unlocks for a year” as a good reason to buy them, along with other shiny newcoin things, fresh chart, concentrated attention, etc.

To make matters worse — other market actors did become more sophisticated regarding these dynamics. Teams, exchanges, market makers and financiers all adapted to these market mechanics, often using them to their significant advantage.

As a result, it seems to me that the majority of new launches are now effectively uninvestable at market – and market participants’ understanding of the issues is extremely under-evolved, where they spend their time pointing the finger at symptoms of the problem.

In this multi-post series, I’ll explore some of the issues in the current market for new launches and discuss some of the reasons why I would default to staying away from new tokens launches entirely – unless you know what you’re doing and are comfortable doing proper research and analysis.

The majority of upside for new tokens is now being captured privately

In the modern era, virtually the entirety of the asset’s “price discovery” has occurred off-market, being captured privately before the token even exists. And a lot of this price discovery is actually inflated due to private market dynamics.

It is funny to reflect that by 2024 people would be yearning for ICOs once again. It is hard to disagree with them when you take a look at the difference in opportunity between now and then: in certain ways, the ICO era seems significantly fairer than the current dynamic of the market.

Rewinding to ICOs: the bad

Before I am misunderstood, I believe it’s important to stress that ICOs were also actually very bad for a bunch of reasons. It’s easy to look back on the successful ICOs, but there were hundreds that just extracted 8 figures and left or slowly rugged. (Also, I am also overlooking that ICOs are also likely illegal in most major jurisdictions).

Retail investors wasted hundreds of millions of dollars funding non-viable, dogshit ideas that were solely able to fundraise because of the ICO craze.

Even successful products that had ICOs left investors rugged. There are dead tokens for many otherwise successful businesses where investors received a token that went to 0, and the company received dilution-free funding for their business before simply ignoring that the token exists after a while.

(This kinda even happened in the Binance ICO — investors funded $15m for the building of Binance but received no upside in Binance equity for doing so. Of course, I am sure that nobody who purchased the Binance ICO is complaining since the price was 15 cents per BNB and it was one of the best performing ICOs ever. So, uh, yeah.)

ICOs: the good

Alright, so ICOs were bad, we get it. But they were also kinda good too. And it’s much easier to display why they were good.

Ethereum raised $16m in their ICO, selling 83% of the supply at the time (60 million ETH) for $0.31 per ETH.

This prices the public token sale at an effective valuation of around $26m (the mining and staking emissions make it a little more complex but ballpark).

Buyers of the ETH ICO received a ~10,000x return in USD (around a 70x return in BTC terms) at today’s prices.

If you missed the ETH ICO, the cheapest you could ever buy ETH on the market was $0.433 in October 2015, only about 1.5x higher than the public sale price. At that time, Ethereum’s valuation was around $35m.

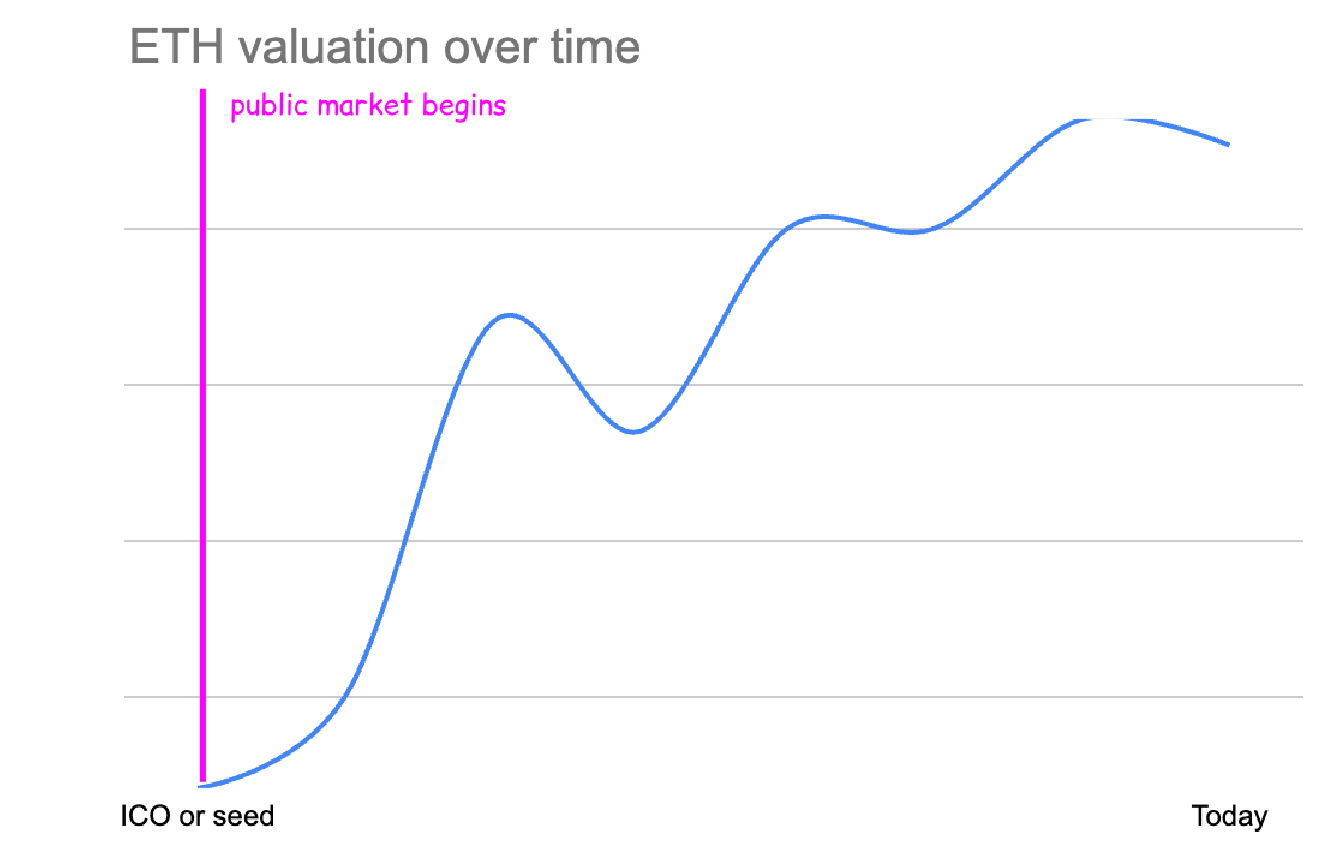

While Ethereum’s $26m valuation pricing is virtually impossible to find in crypto investing anymore, even for a privileged-access seed round of the dumbest idea you ever heard of, the key point here is that price discovery and upside was open for all participants.

The price discovery from $26 million dollar valuation to $350 billion happened in public, in a way that a regular person could participate in. There was no KOL round, no unlocks and vesting schedules and buying the cheapest ever market price resulted in very similar returns to buying the ICO.

Moving to private funding

After enforcement from major global regulators against ICOs, crypto token issuers stopped raising money from the public and instead moved towards private funding from VCs.

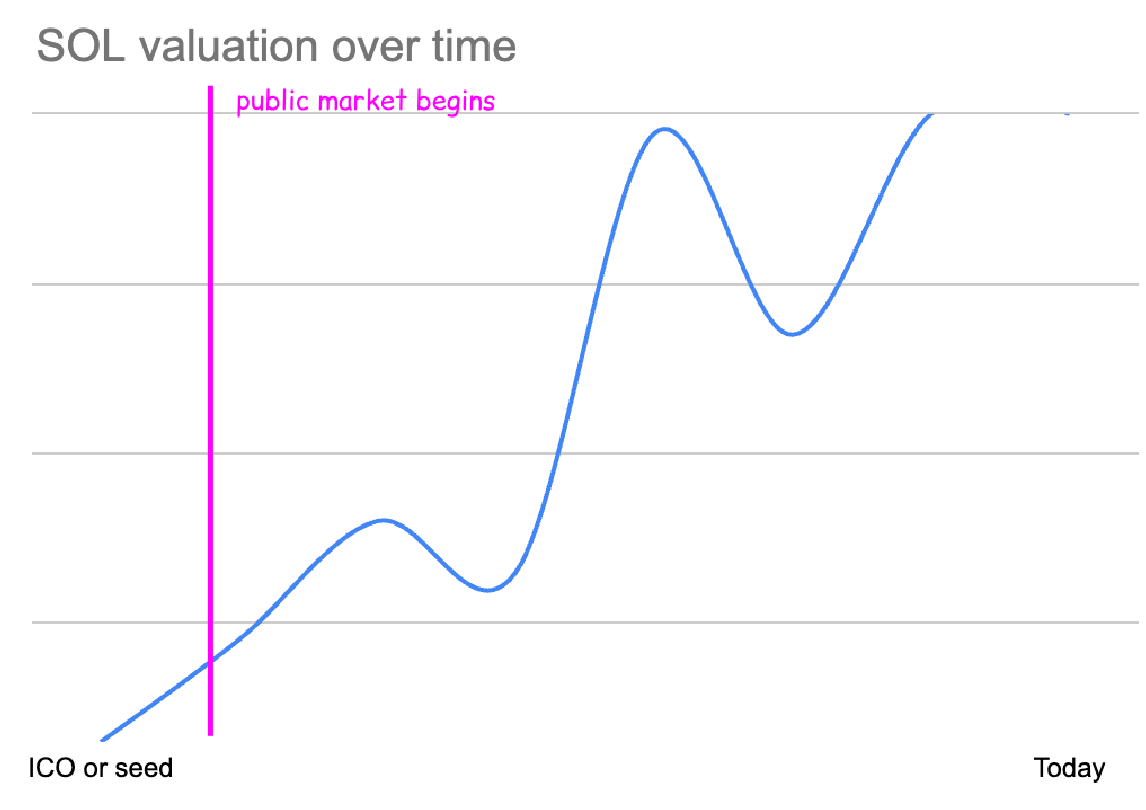

If you compare Solana’s first funding round in 2018 to Ethereum’s ICO, it’s sort of interesting.

Solana raised ~$3.2m in this funding round, selling around 15% of the supply at the time for $0.04 per SOL. This was an effective ~$20m valuation, similar to the ETH ICO valuation.

Buyers of the SOL seed round received a ~4,000x return in USD at today’s prices. (It’s likely they actually received slightly higher due to the annual staking returns, too).

If you were unable to access the limited funding rounds, the cheapest price you could ever buy SOL on the market was around $0.50 in May 2020 — about 12x higher than the seed round.

Buying the cheapest ever market price resulted in ~300x return. At the time, Solana had a valuation of around $240m and a float of below 5%. Solana only really had a low float for about 10 months — they went from having a tiny float to basically being almost fully unlocked with one huge cliff unlock in January 2021.

The initial rounds being privileged allowed investors to effectively capture 10x of Solana’s price increase ($0.04→$0.5) in private.

(Solana also did some other privileged/private funding rounds too, around $0.20, as well as a CoinList “auction-style” limited public token sale, which was also around $0.20 I believe.)

2021 mania

Solana launched in 2020, basically near enough at the BTC and ETH price lows after the COVID crash. Their gigantic unlocks occurred perfectly in sync with a new wave of users being onboarded to crypto. The resulting success of this model across a variety of tokens, and the “bullish unlocks” phenomenon, led to a huge increase in private market valuations.

ETH and SOL’s initial sales were both around a $20m valuation. By 2021, seed rounds were highly competitive with large VCs often entering in bidding wars. Seed round prices reached 100s of millions.

(I remember the first time I was pitched a seed round at $100m. I passed in revulsion. Later the project opened at $4bn FDV and I missed out on a 40x. Learning from my mistake, I bought the next 100m seed round that came across my desk. It failed and went to 0 and is no longer active).

While private market valuations were rocketing, on the liquid markets side, crypto traders were claiming “FDV is a meme” while all charts were effectively green lines to the sky.

Axie Infinity was valued at something like $50 billion, despite only having around 20% of the coins circulating at the time. FileCoin reached something like $475 billion FDV, but a market cap of $12 billion. The increase in supply for high FDV coins were masked by the huge waves of new entrants.

As fully-diluted valuations reached larger figures, VCs became increasingly willing to pay more for private rounds too — “if this project is trading at 15 billion then bidding a round for this other one at $300m is okay, it is a bigger risk to miss out!”.

Founders, of course, willingly accepted these bids — they could raise more money and give away less tokens for doing so. They previously had to sell 10% at a $20m valuation to raise $2m. Now, they can sell 1% to raise $2m, and keep the extra token supply for incentives, community or (...surprise!) for themselves.

If a reputable VC funded a promising project at a $100m valuation, many less-respected VCs would attempt to copytrade them. If the last funding round for a project was at $100m, these thesisless chaser VCs would try to lead a new round at $300-500m as soon as possible. The slightly worse entry didn’t really matter to them, these things were trading at multi-billions anyway.

Founders could easily accept these deals. It made their personal wealth “watermark” higher without requiring market forces, and it added new team players to their side to help their product win. Of course, most of these team players turned out to be net negative, but founders were not to know that yet.

Through this pattern, as time passed, even more of the value and price discovery has been captured privately.

Private capture

If we take the Ethereum and Solana examples from earlier, and consider them when compared to projects that launched in more recent years. I’m going to choose two comparable projects: Optimism and Starknet.

Consider the following metrics: initial sale valuation, lowest valuation ever on market, % float at that time, returns from market vs. private.

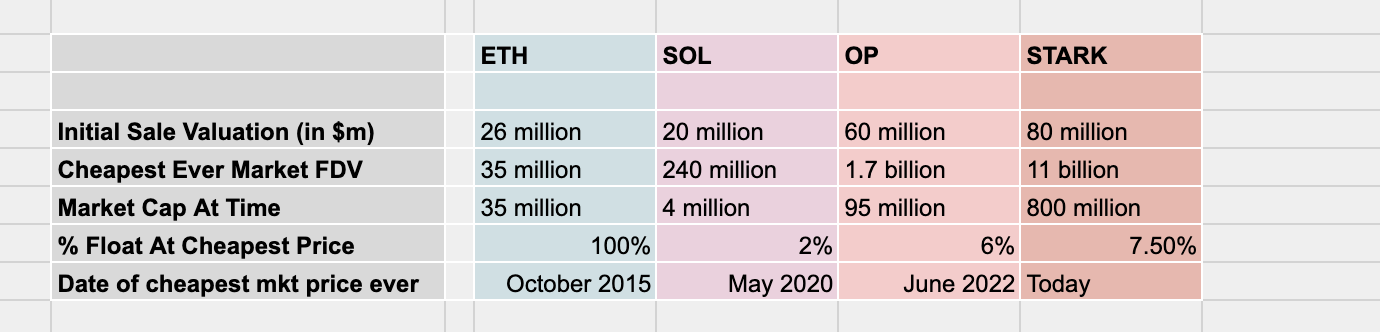

ETH ICO valuation: $26m

ETH’s lowest ever open-market valuation: $35m FDV

Date of lowest market val: October 2015

Float at that time: 100% supply on market — market cap $35m.

Returns from public sale: 10,000x

Returns from market: 7,500x

SOL seed valuation: $20m

SOL’s lowest ever open-market valuation: $240m FDV

Date of lowest market val: May 2020

Float at that time: 2% supply on market — market cap $4m.

Returns from private seed round: 4000x

Returns from market: 300x

OP seed valuation: $60m

OP’s lowest ever open-market valuation: $1.7 billion FDV

Date of lowest market val: June 2022

Float at that time: 6% supply on market — market cap $95m.

Returns from seed round: 183x

Returns from market: 6x

STRK seed valuation: $80m

STRK’s lowest ever open-market valuation: $11 billion FDV

Date of lowest market val: today

Float at that time: 7.5% supply on market — market cap $800m

Returns from seed round: 138x

Returns from market: none

If you take a look at these metrics, a few things are clear. Firstly, seed valuations have increased a lot as time passes.

Ethereum’s ICO was at ~$26m.

Solana’s seed round was at ~$20m FDV.

Optimism’s seed round was at ~$60m FDV.

StarkNet’s seed round was at ~$80m FDV.

Modern seed rounds for comparable projects are now >$100m FDV.

As the seed valuation moves up, the team captures this multiple, as they still own the entirety of the supply until the first funding round. If StarkNet were valued at the same as Ethereum, the initial investors would still have a worse financial return since their initial entry price was 4x higher.

Honestly, I find this pretty inoffensive by itself.

It makes sense to me that, as crypto has become more popular and the financial returns of Bitcoin and Ethereum have been proven over time, founders would have better fundraising options. The demand for early stage crypto investments is gigantic, so prices adjust naturally.

But the most glaring trend evident in the data presented above is that the financial returns from public markets are diverging hugely from the financial returns available in private markets.

Ethereum’s ICO returns were 1.5x higher than available on market.

Solana’s seed round returns were 10x higher than those available on market.

OP’s seed round returns were 30x higher than those available on market.

STRK’s seed round returns are infinity times higher than those available at market, because today is STRK’s lowest ever price, meaning all public market buyers have lost money — but the seed is up 138x.

As you can see, the returns are increasingly captured in private.

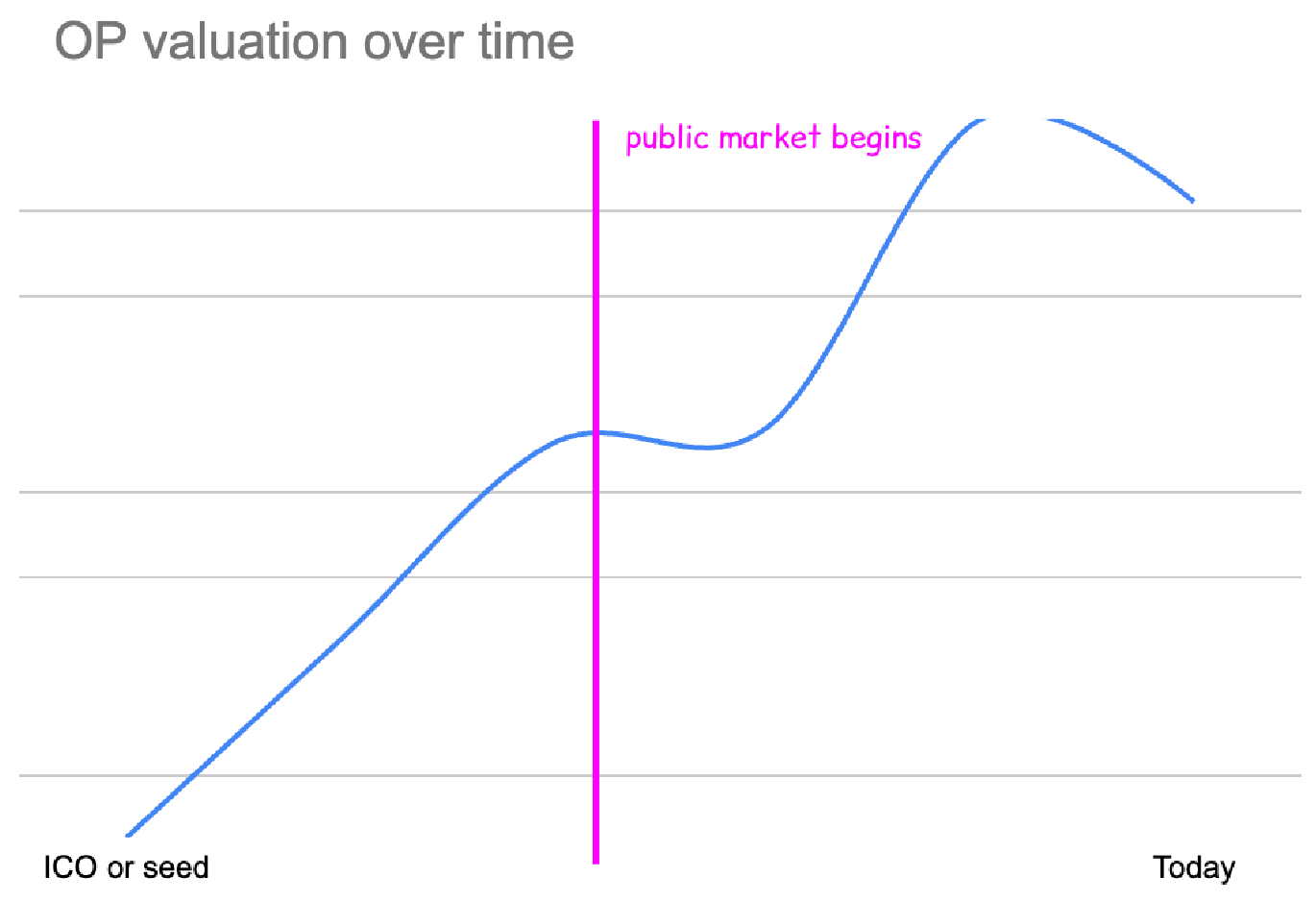

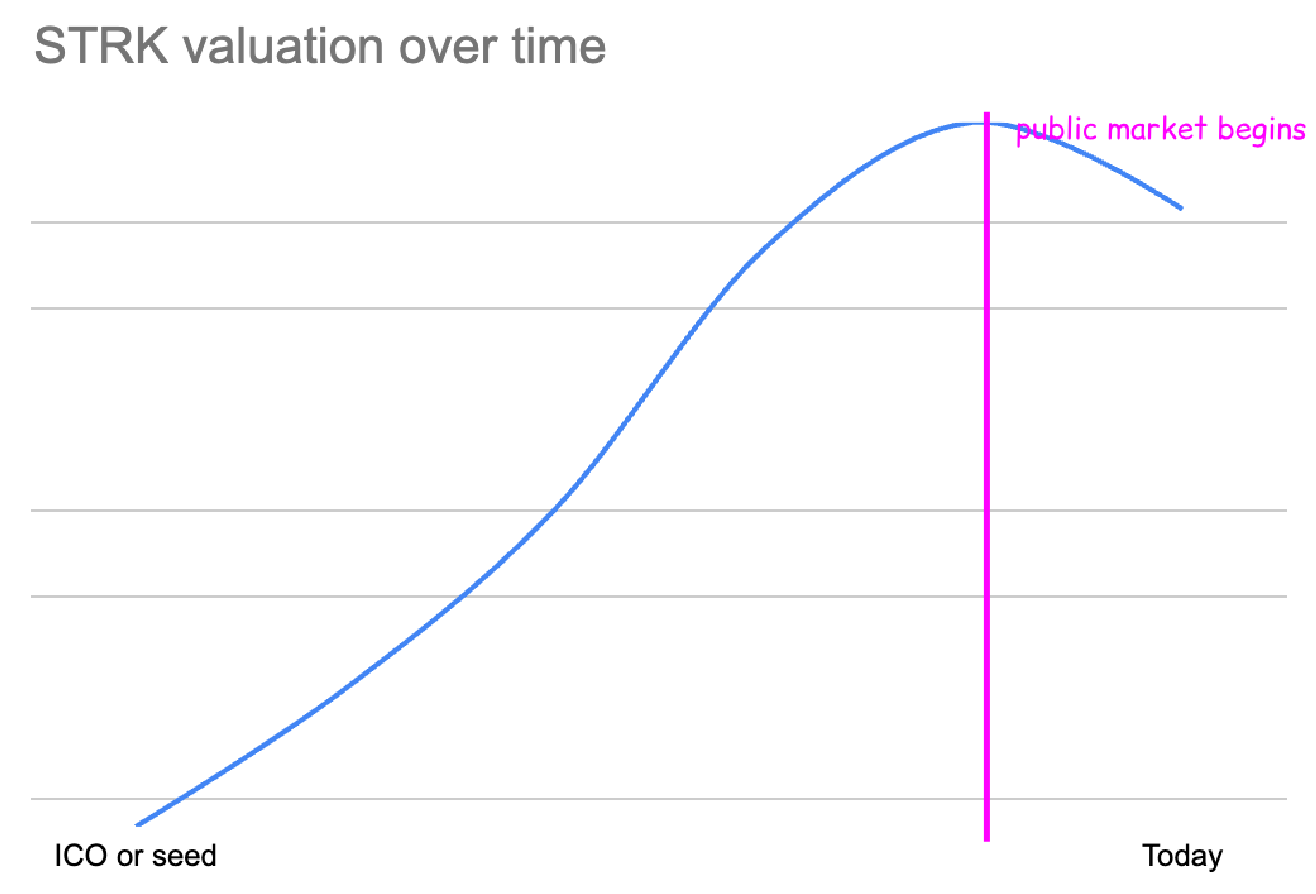

To visualise, consider the private fundraising rounds of the tokens I mentioned earlier:

Ethereum has an ICO selling 80% of tokens, and no other funding rounds.

Solana had a seed round selling 15% of tokens, and a couple of other private rounds pre-TGE up to about $80m FDV.

OP had it’s seed at ~$60m, and then had private fundraising rounds at ~$300m and ~$1.5bn FDV before TGE.

STRK had it’s seed round at $80m FDV and then also had funding rounds at ~$240m FDV, ~$1bn FDV and ~$8bn FDVs before TGE.

If you imagine a price chart for each of these assets, but try to visualise the private market prices on the chart too. (valuation in logarithmic scale).

All charts start at roughly a similar valuation (20-80m range), but increasingly the majority of this uptrend is captured by private markets.

Both OP and STRK have a similar current market valuation ($11bn) and yet OP has had to achieve a public market 6x to reach $11bn. STRK has dropped 50% to get here.

To reach 11bn, SOL had to achieve a public market 50x, and Ethereum had to achieve a gigantic public market 450x return.

Crypto token investment opportunities with returns akin to the ETH ICO still happen very regularly, but they are nearly entirely captured privately now.

High FDVs are in part due to natural market demand

Expecting launch FDVs to be in line with launch FDVs from 4 years ago is not an expectation grounded in reality.

The amount of capital in the space has increased 100x, the stablecoin supply has increased 100x, the amount of demand for new good crypto tokens has increased 100x, and so on. New tokens will launch higher because the market demand is much higher now, and comparable projects are valued much higher too.

When looking at FDVs, consider their price appropriate to the rest of the market.

Solana’s launch FDV was around $500m.

At that time, it would’ve placed Solana into the top 25 coins that existed.

It would have been valued at ¼ of BNB’s valuation, which was a top 10 coin at the time.

It launched when Ethereum was $150 per ETH.

It launched when the ETHBTC ratio was 0.02.

I am using the ETHBTC ratio here to display market confidence and demand in both Ethereum and the smart-contract chain thesis, which were at historic lows. The doubt around “alt L1s” was even greater. There had been serial failed attempts at “ETH killers”.

Since then, ETH is up 20x, BTC is up 10x, SOL is up 138x, the general market has priced up hugely and the confidence in smart contract chains as alternatives to Ethereum is at all time high.

Today:

A top 25 coin would be >$5 billion market cap, ~10x higher than when Solana launched.

¼ of BNB’s valuation is now ~$9bn market cap, ~20x higher than when Solana launched.

ETH is $3100, ~20x higher than when Solana launched.

ETHBTC ratio is 0.046, over 2x higher than when Solana launched.

If Solana were to launch today, using these comparable metrics as proxy for demand, the FDV upon launch would likely be around $10bn – and this may even be underpricing due to these proxy metrics not considering the popularity of alt L1s.

Similarly, when Avalanche launched in September 2020:

Avalanche launch FDV was around $2.2bn.

At that time, it would’ve placed AVAX into the top 15 coins that existed.

It would’ve been valued at ½ of BNB’s valuation, which was a top 5 coin at the time.

It launched when Ethereum was $350 per ETH.

It launched when the ETHBTC ratio was around 0.03.

Re-calculating the launch today, using modern prices, would have had Avalanche launching at $15-20bn.

Post-crisis prices

Another way to visualise this is to consider Solana’s picolow valuation in 2022, after the FTX collapse and the demolition of investor confidence.

The valuation of Solana, at the lowest price in a heavily depressed market, was around $5bn. This valuation was one of the best liquid investment opportunities in the last few years, and was only achieved through an absolute exorcism of fraud and leverage in markets.

Markets have significantly rebounded since then. An Ethereum ICO, if held today, would not only raise $16m. The Solana seed round, if held today, would have billions of dollars in demand.

It’s nice that you want to buy things at prices from 5-10 years ago, but it is sort of like saying “I want to buy Ethereum at $150”. Yeah, who doesn’t?

Older rounds and previous launch FDVs were priced relative to the amount of risk taken, the amount of confidence in those assets and in crypto in general. The demand for those older funding rounds was significantly lower and so they were priced for that demand.

Projects I funded even in late 2020 were struggling to fill their $2-3m funding rounds at tiny valuations. Now, seed rounds for “Pin the tail on the donkey — but on the blockchain” are oversubscribed just by calling themselves “gamefi”.

Think about it like this: if the Solana founders released a new blockchain tomorrow, what valuation would you be willing to buy it at? Would you pay at least a quarter of the current Solana valuation ($25bn FDV)? Maybe even half of SOL’s valuation ($50bn FDV)?

Of course, the FDV would be very high at even 10% of Solana’s current valuation, because market demand would be very high. And so yes, FDVs are higher now, because the entire market is worth a lot more than it previously was and there is significantly more demand.

Of course, a high FDV is certainly not always indicative of demand in the market for that particular asset. And a high FDV is not always justified or earned.

Recently in particular, it is often not. Market actors have figured out ways to use these levers to their advantage and pin valuations at inflated levels.

One of the bigger issues in the market is not that FDVs are higher on average — but it’s that many new launches have a high FDV detached from the reality of the asset and they simply try to blend in amongst the other high FDVs.

It has become normalised to launch at multi-billions, even if that valuation cannot be justified by any real data, and projects that may never justify these valuations are apparently indistinguishable from better ones to many market participants.

Low float is not to blame in isolation

Low float by itself is not inherently a bad thing, and a low float by itself does not create an unhealthy market or represent bad actor status – it is just a variable that investors must consider. Plenty of low-float tokens had good launches and healthy market dynamics.

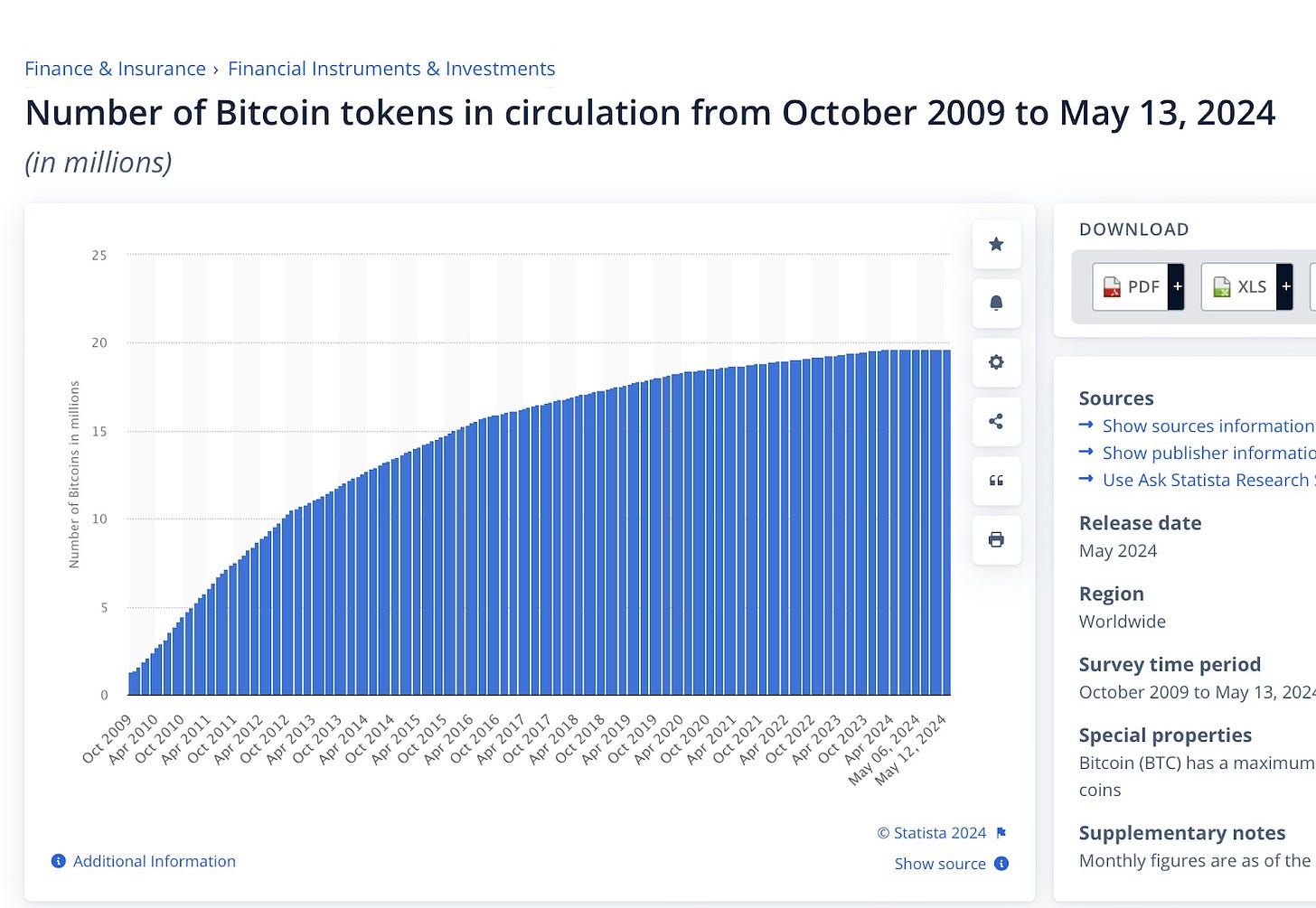

Bitcoin’s emission schedule is extremely well-known, with the halving reducing the supply of new coins on the market every four years. Bitcoin’s “float” was <10% for it’s entire first year after the genesis block.

Solana’s first year float was also very small, before gigantic unlocks 10 months later.

To be clear, I don’t mean to argue in favour of low floats.

I believe a higher float is virtually always healthier for tokens, and I respect projects that have tried to reach 100% float quickly. (There doesn’t seem to be a great way to get more float to market, and projects that have managed it have often done so against their own best interests in the short-term).

I am merely suggesting that a lower float alone is not some glaring red flag, if your evaluation other important factors returns good results. And similarly, a higher float does not instantly symbolise green flag, or imply it is going to be a “better investment” either.

Where the dynamics of low float do become problematic is when paired with other issues. Unwarranted and inflated FDVs, perverse agreements with other market actors, or active manipulation from bad actors.

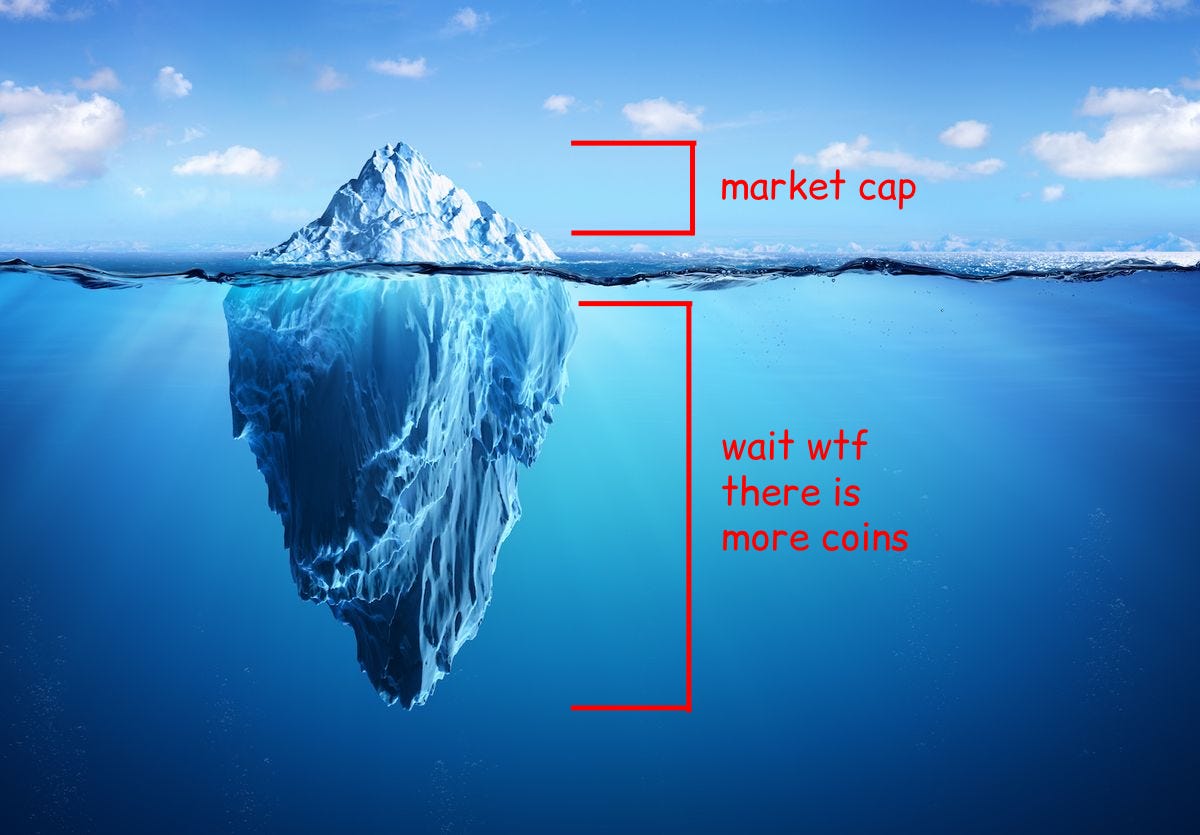

A low float market is much easier to manipulate and distort when misappropriated by bad actors – for example, the lower the float, the lower dollar-demand required to pin a token at a high valuation.

And yes, low floats can also cause dislocation between valuations and reality when the float or FDV is misunderstood or ignored by under-researched token buyers. The existence of valuation-agnostic buyers seems very unlikely to me. It seems more probable that token buyers simply do not review or consider these metrics at all.

To protect and inform themselves, token buyers need to evaluate the equilibrium between the float, the FDV, and the demand for the coins that are unlocking. They should consider: what is the cost basis of the locked supply, what is the OTC demand like for locked coins in private markets, and how eager are the existing holders to sell those locked coins.

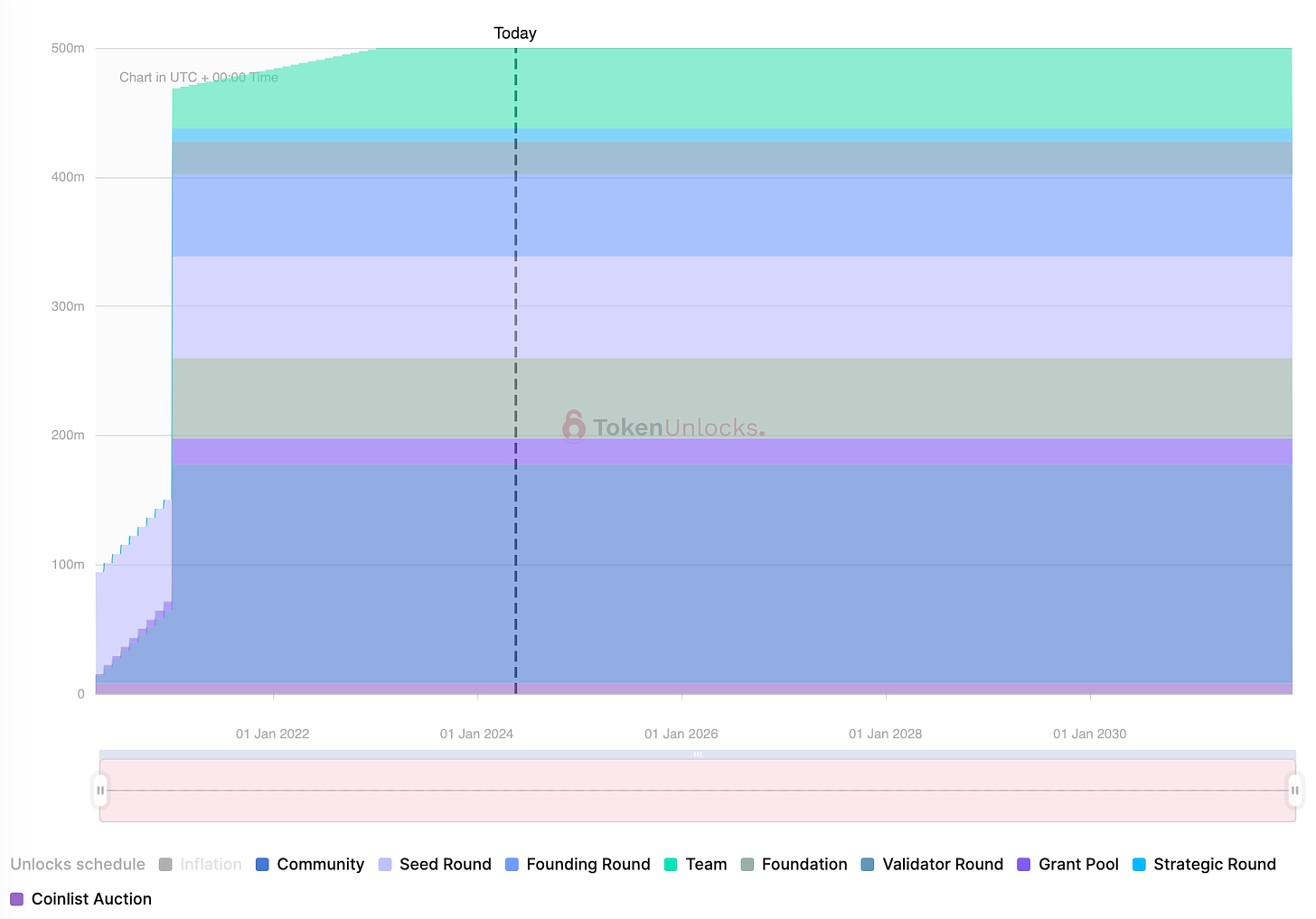

Finally, a reported high float could itself be a low float.

A demonstration of this, from what I believe is likely an innocent example, could be this recent popular token launch:

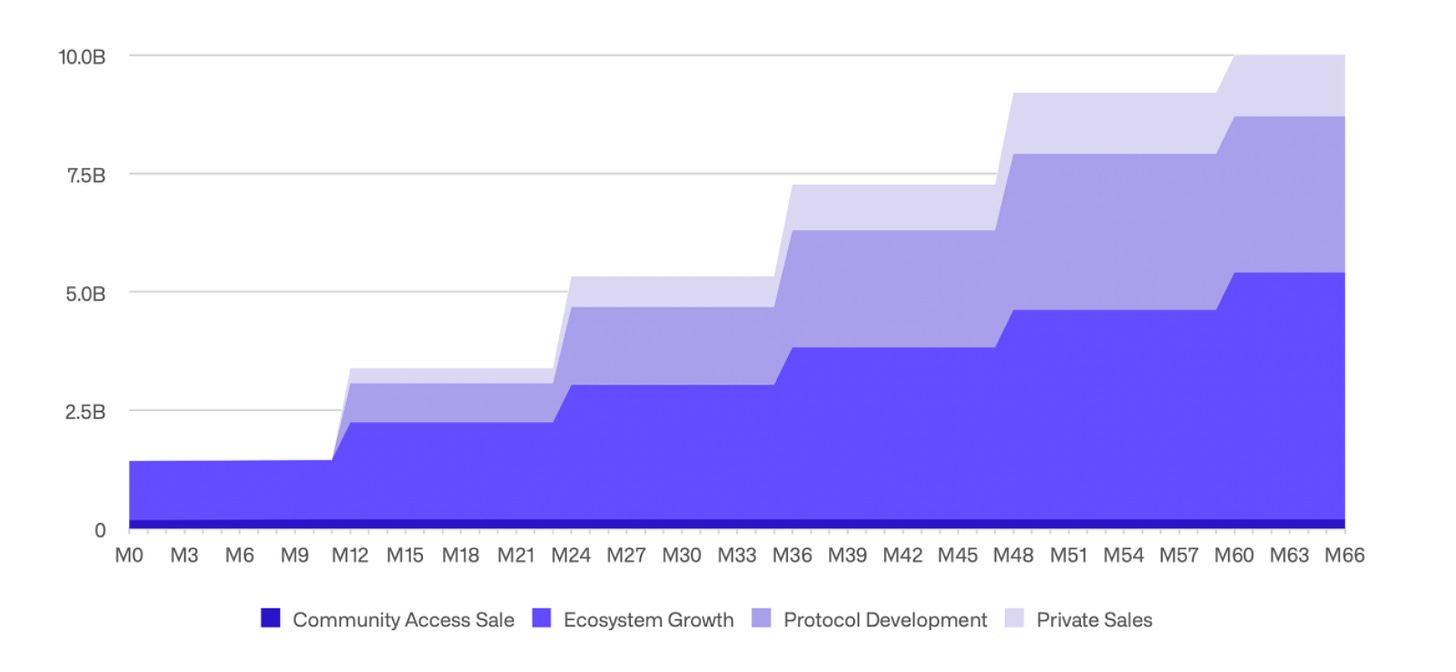

From this chart, you see that ~15% of the float is unlocked.

On closer inspection, you’ll see only ~2% attributed to “community sale”. The remaining unlocked float is attributed to “ecosystem growth fund” which is described as a strategic portion of tokens set aside for growth incentives such as airdrops and for contributors to the project’s ecosystem, including developers, educators, researchers, and strategic contributors.

It is impossible as an outsider to know how this ecosystem portion will be allocated. We do not even know if any of this portion has been allocated at all. The real (sellable) float for this token may only be around 2-3% — despite 15% being reported as the unlocked float. This may imply the market cap is almost 90% lower than stated due to the inactive supply and off-market being included in the float.

This demonstrates that assessing the unlocked float % alone is not enough. In fact, obfuscating and over-inflating the real (trading) float size may actually be a superior technique from bad actors, particularly if market participants default to thinking “low float = bad”.

Token buyers should research who holds the unlocked supply, how it is being used and whether they can distribute that supply or not.

This “private price discovery” takes place in a rigged market and the resulting valuation is deceptive

In my mind, one of the primary issues at the heart of the low float/high fdv debate lies here.

The issues people have with “low-float” or “high FDV” is in fact actually because the price discovery has taken place in a private market that is either rigged, delusional or both.

Allow me to introduce – the phantom market. (I wanted to call it the shadow realm but I am trying to not get addicted to yugioh again).

Imagine a market where one person, we will call him Kain, controls all of the supply of a new token. In this market, anybody is allowed to bid, but only Kain is allowed to sell.

Kain sells some tokens to a new investor, called Adam, at a $50m valuation. Adam’s tokens are locked and not transferable. Kain sells more tokens to a new investor, Eve, at $300m valuation. Eve’s tokens are also locked and not transferable.

Adam and Eve have a great reputation as investors (perhaps due to fame from The Bible?) and so other investors become interested in Kain’s token too.

Kyle, Bob and Taylor Swift are all bidding for the next round at $1bn valuation – Kain decides Bob is the best investor here, Bob buys locked tokens too.

Hurt from rejection and too afraid to miss out on this fantastic new token, Kyle bids at a $2.5bn valuation and Kain sells some locked tokens to him.

At this point in time, Adam’s investment is up 50x. He is desperate to sell. He has been larping writing twitter threads for the past several years and this is finally a big win for him. In fact, he would even have been happy to sell at the $1bn valuation from the previous round.

Eve’s position is up around 10x and she is happy to sell anywhere above a $1bn valuation too.

But since these holders are not allowed to sell – and the one guy who is allowed to sell doesn’t really have many reasons he would ever want to sell lower – it’s a market that is rigged to only go up.

This “phantom market” that happens pre-token is a delusion. It is not discovering the natural price based on the dynamics of supply and demand. It is simply finding the absolute highest price that a VC investor is willing to pay. This dynamic pushes valuations to prices that the market is unable to bear, evidenced by the graveyard of tokens from 2020-2022 that are trading significantly below their private market valuations.

When Kain’s token reaches Binance or Coinbase, the phantom market does not stop but evolves a little.

Imagine Kain’s token is now trading at a 5bn valuation. Even Kyle who panic-bought late is up 2x. Every single investor would now be happy to sell their tokens – perhaps Kain has now been accused of some nefarious things behind closed doors, or some new kid has designed a better version of Kain’s product.

The investors, eager to sell, unable to sell their locked tokens on the market. They are not able to exit their positions until their unlocks/vesting hits. So, once again, these investors attempt to use private markets – sourcing OTC demand at a 60% discount to market price.

Now the real market is priced at 5bn. But in the phantom market, tokens are trading at $2bn valuation.

This dislocation between the liquid token price, and the locked token price is the real issue in low float coins.

If the phantom market price is significantly lower than the real price for a token with a low float, the unlocks are clearly going to be exceedingly painful.

(On the other hand, if the phantom market price is close to the real price, then the low float and upcoming unlocks might not mean very much. I’m told locked Solana was trading at only a 15% discount to unlocked Solana at times just before their major unlock – and nearly the entirety of the locked SOL tokens had been bought by MultiCoin, Jump, Alameda, or someone else.)

Price discovery in public creates much healthier markets.

The reason unlocks dump so much in certain assets is because price discovery never actually happened — it just tested what was the highest possible bidder’s price was.

The phantom market price was hugely dislocated from the real price. Most market participants have no way to track the phantom price, meaning it’s extremely difficult for them to evaluate the expected pain from unlocks for any given asset.

Opting out

Part 2 and 3 of this series will explore incentive structures for a variety of other market participants, and use these to further explain the dynamics of new launches. Specifically, who is benefitting, and why new launches are able to maintain such inflated valuations.

These sequels will also discuss ideas and solutions to existing market dynamics that good actors can use to create healthier markets — and will also discuss why that is in their interest to do.

However, meanwhile, there is a simple suggestion I can recommend for readers that do not have power to change structural dynamics at the infrastructural level.

Buying an inflated FDV is your choice – you can opt out, and you probably should

This seems obvious, of course, but the “invest, then investigate” mantra does not seem as suitable to as many of you seem to believe. Either that, or maybe you’re skipping the investigate part.

Token market cap info, and FDV info, is always public — unlocks are typically documented in public somewhere too as long as the project is half-decent. The tokenomics often show who owns the supply. It is harder to find private round prices, but it’s possible.

If any of these basic parts of information are missing — this is a red flag! If any of these basic parts of information seem confusing or obfuscated — this is a signficant red flag.

You do not have to buy these tokens, even if you think the project is good.

In fact, opting out and protesting with lack of participation seems like the correct response to a lot of recent token launches.

Projects, founders, exchanges, and other market actors will have to adjust their go-to-market strategies if the existing ones are failing, or they are being rejected by the market.

I am already seeing projects adjusting their launch and fundraising token plans due to the popularity of memecoins and the rejection of the recent launch meta.

Token buyers should research valuations before buying and, if they don’t like the valuation, then they should refuse to play.

If you think a new project is the greatest idea on earth and you want exposure, it remains important to evaluate the valuation and unlock schedule. It’s possible that great projects have bad token dynamics until they are fully diluted, or perhaps that the valuation is just way too high for it to be investable at that moment in time.

It is currently not possible to “be early” to new token launches — as we have seen, the private capture of upside happened in an inaccessible way.

Instead of trying to be early, it is better to be disciplined and patient. Identifying projects you’re interested in, and assessing valuations where they become attractive seems significantly preferable than joining your latest CEX-affiliated CT influencer in longing the perps of a coin that launched 30 minutes ago.

The good news is that for most of these tokens (good project, but lots of unlock or VC overhang, or potentially bad token dynamics for a couple of years) is that market actors can learn the wrong lesson about these assets, write them off entirely during their early periods of turbulence periods — perhaps rewarding you with a better-than-expected entry later.

In sum

New launches have become uninvestable, mostly due to the privatisation of price discovery and unhealthy inflated valuations from VC markets that ignore supply and demand. These market dynamics are possible to exploit by disreputable actors, and sophisticated market participants are increasingly using them to their advantage.

While FDVs are higher than years ago, popular and hyped new launches have always priced the FDV of tokens within the top valuations of the market. This has been the case for at least the last 5 years — and this is mostly due to the privatisation of the price discovery.

The “upside” captured by projects like Avalanche and Solana since their launches were:

Partially driven by overall market returns.

Avalanche’s performance since it’s public market debut until today is ~7x whereas Ethereum is around 9x on the same timeframe.

But also driven by additional repricing from their position within the market.

Solana moved from top 25 to top 5, creating a significant repricing vs ETH and rest-of-market.

Avalanche moved from top 15 to top 10 before moving back down, causing a temporary repricing vs ETH (and rest of market) during the bullrun, which has since been erased.

When evaluating the upside in new tokens, token buyers should consider both the new token’s FDV vs. the rest of the market — but also the trajectory of the overall market.

If a new launch’s valuation places it in the top 3 of all coins in existence then for this investment to perform well the investor would need a large market-wide expansion, and for the project to retain it’s status in the top 3, since it does not have much room to grow relative to the market.

If a new launch’s valuation places it in the top 30, and an investor believes it to be a top 10 project, then a low float and higher FDV would perhaps hold less importance when evaluating the token.

While a launch at 10bn seems expensive today — if Solana is at $1000 and worth $1 trillion in a couple of years, then yeah maybe $10bn will look cheap in hindsight, and people will be complaining that new launches are all at $80bn.

Judging new token launches by the first couple of months performance can also be a red herring – Solana dropped 50% from listing price and didn’t recover to it’s initial price for a couple of months. It took the inflows of new capital in the bullrun for Solana to reprice it’s position in the market.

Significant early market repricings are unlikely without an ongoing market-wide trend, since a) private markets extract the upside b) it’s difficult to fight market forces to underprice something in a high-demand market, and c) it is possible for projects, exchanges and market makers to fight market forces to overprice something if the float is very low.

Market participants should expect that new launch valuations remain high while the market is in demand. It is no longer possible to be “early” in the privatised-gains meta — instead investors should focus on finding value in the market that others have forgotten, or has become mispriced and out of favour.

Token buyers should aim to become more sophisticated at evaluating the valuation and supply/demand dynamics of new tokens, identifying which high FDVs are based in supply/demand realities, and which have extremely dislocated phantom markets.

Opting out of participating in these markets is voting with capital.

Good founders want to build successful projects and they know that market dynamics will interact with their project’s perception. Memecoin over-performance and new token launch under-performance has caused readjustments in fundraising and launch plans for future founders.

See you soon for part 2, more problems, maybe some solutions, who knows. I don’t know how long this post was. I’m scared to check. I apologise to all of you.

Thanks for coming back just right in time ser🫡

It is a pleasure to read a new article of yours, Cobie. You have been missed on Substack !